UK: Victims of modern slavery missing out on vital support and left facing homelessness

Current UK Government support for people experiencing modern slavery is leaving many victims without a safe home, facing life on the streets with no way out and at risk of further exploitation, a new research report led by homeless charity Crisis has shown.

The ‘No way out and no way home’ report, which has been published today, shows that less than half of homeless survivors of modern slavery in England, Wales and Northern Ireland were referred into the government’s support system, the National Referral Mechanism (NRM), with a further 45% explicitly refusing to be referred.

This leaves victims without access to vital support such as accommodation and legal advice, meaning many are left trapped in homelessness and at risk of being forced back into slavery, all whilst dealing with the trauma of their experiences.

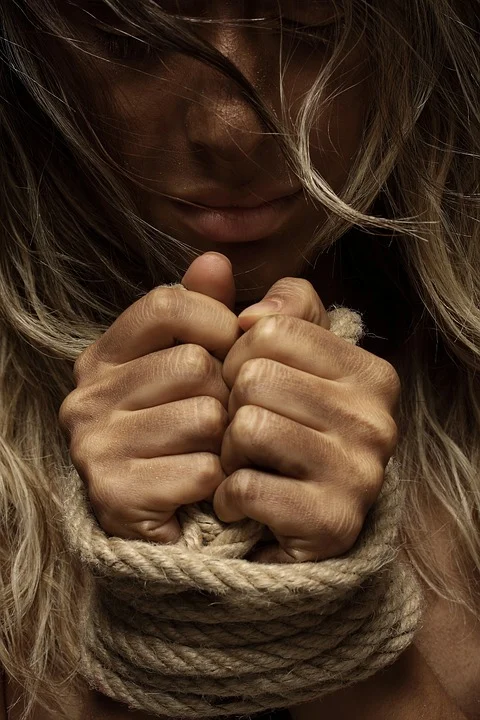

Modern slavery is when people are forced by others into a situation that they cannot leave so that these perpetrators can exploit them for profit.

The most common types of exploitation identified in this research were sexual exploitation (43% of cases), followed by labour exploitation such as working in construction (25%) and forced criminality such as theft (18%).

This research comes from Project TILI, a Crisis-led research project working with partners Hestia, BAWSO, Belfast Women’s Aid and Shared Lives Plus. The project aims to better understand and build evidence on the close links between modern slavery and homelessness across the UK, and how both can act as a route into the other.

The findings of the report come from the experiences of over 330 people affected by homelessness and modern slavery who have been identified by different support organisations across the country over the past two years.

The report also identified insecure housing as a key issue related to modern slavery, with nearly two-thirds (65%) of victims living in accommodation linked to their abusers whilst their exploitation was ongoing.

For those who were referred for support as part of the NRM, only a fifth (17%) of survivors were in secure permanent accommodation upon exiting the system and a further fifth were still homeless and at risk of re-exploitation, illustrating how closely homelessness and modern slavery are interlinked.

Additional findings of the report include:

- The most common nationality of survivors was British (34%), followed by Albanian (12%), Romanian (8%), Nigerian and Polish (7% each)

- People experiencing exploitation were more likely to be younger, over half (55 %) of people were aged 34 and under, and only 13% were aged 55 and above

- Women were more likely to experience domestic servitude, forced marriage and sexual exploitation over other forms of exploitation, whereas the majority of forced criminality and labour exploitation was experienced by men.

Christopher, who is in his 30s and from Croydon experienced modern slavery himself, starting four years ago. Christopher is originally from Brazil but has been in the UK for six years. After his visa ran out Christopher was left with no immigration status or right to support so when he had to leave a violent relationship in 2017 and had nowhere to stay, he became a victim of modern slavery. Crisis is now working with Christopher to help him with a safe place to stay and confirm his immigration status.

Talking about his experiences of modern slavery, Christopher said: “In my relationship, I was living with a person that meant it wasn’t safe for me anymore and I had to leave. I had no recourse to public funds or legal status. I met a guy who said he would arrange a place for me to stay and I had to do sex work there. I had to pay £800 a week to live there - and because he knew I had no confirmed immigration status here he charged me more and changed the price all the time.

“I knew it was the only way I could have a flat without immigration status though. All the flats in the building belonged to this man and he rented out the whole building to people in this same way - none of them had status either and he just did what he wanted.

“This man took all the dignity out of my life. After three years I was suffering a lot with addiction and my mental health so I told him I didn’t want to do sex work anymore. I left and when I came back he had his friends there, had changed the locks and thrown people out. I was so scared and he knew I could not go to the police. That was when I became homeless and ended up living on the streets.

“I can see now that my experiences were modern slavery and I understand how lucrative it was for this man.”

Crisis is now calling on the Westminster government to address the issues highlighted in this report to make sure that the right support is made available to victims of modern slavery at risk of homelessness and vice versa, so that more people do not have to experience the trauma of either in the future.

Jon Sparkes, chief executive of Crisis, commented: “Modern slavery exploits our common need to work to sustain ourselves and build our lives. Everyday through our frontline services at Crisis, we hear of people experiencing homelessness who have faced exploitation – forced to take part in sex work, work as a live-in servant or take part in crippling manual labour, working all hours of the day for little to no money, scared and feeling there is no way out. The impact this abuse has on a person is simply unimaginable.

“Until now, the links between homelessness and modern slavery have been mostly anecdotal with very little research completed in this area. This report provides us with the clear evidence to show how the two drive one another and more importantly, what we need to do to prevent both and end the cycle of people trapped in the most dreadful of circumstances.

“We urgently need to see the Westminster Government passing the Modern Slavery Bill as soon as possible, ensuring survivors are entitled to at least 12 months of tailored support, including a safe long-term home, following a positive decision. We also need to see the Home Office address the clear issues with the National Referral Mechanism, including further research into the specific reasons victims don’t want to be referred and also offering other means of support for people who don’t want to engage with the system.”