Our Housing Heritage: How Glasgow tenants ‘fought the huns at home’ during World War One

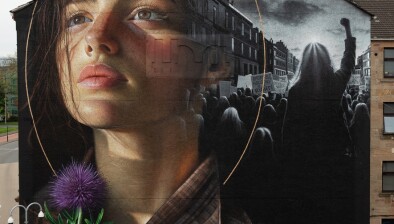

Mary Barbour

In the latest article in the ongoing Our Housing Heritage series, Scottish Housing News discusses the Glasgow Rent Strikes of 1915.

In the absence of social housing, families across the UK in 1915 were at the mercy of private landlords who could hike rents and evict tenants at will with little restriction.

The outbreak of the First World War exacerbated the pre-existing housing shortages across the country as wartime industry drove hordes of workers into industrial cities. Glasgow saw a huge increase in wartime production in shipyards, engineering workshops and munitions factories with newly arrived workers and their families increasing the demand on an inadequate housing supply.

Many of the city’s landlords sought to exploit the situation. In February 1915, Glasgow landlords informed tenants that all rents would be increased by a whopping 25%. A huge proportion of families, especially those whose primary breadwinners’ were fighting in the war could not hope to pay the increased rents.

A statue of Mary Barbour and the rent strikers in Govan

In response, tenants all over the city mobilised to ‘Fight the Hun at Home’, as they characterised profiteering property owners.

In April, tenants decided that they would only pay only their normal rent and refused to comply with the rise in price. Residents in the shipbuilding areas of Govan and Partick signed ‘non-payment petitions’ agreeing to pay the original rent but not the increase. By June, some landlords gave up trying to force tenants to pay up.

Gradually, tenants spread the idea of refusing to pay, with Glasgow’s Labour movement supporting the struggling tenants from the very beginning.

The Labour Party Housing Committee was formed in 1913 and fought for the council to construct homes for workers. At this point, Glasgow already owned its own tramway system and gas works and the committee fought for the profits of these to be utilised for housing efforts.

It took many years for the committee to make progress. But the rent increases being forced on the ordinary workers of Glasgow lit the fire under the movement and led many to fight for change.

Meetings to resist the rent rises were held all over Glasgow and Govan. These meetings led to the birth of the Glasgow Housewives Housing Association (GWHA) under the chairmanship of Mary Barbour. This organisation brought the women of Glasgow to the very forefront of the fight against rent hikes and unfair landlords.

The rent strike was formally initiated in September 1915 and within just two months more than 25,000 working class Glasgow families were refusing to pay their rents. Sheriff officers and bailiffs who attempted to evict the tenants were met with organised resistance and protests by the Housewives Committee.

Tenants threatened with evictions placed ‘WE ARE NOT MOVING’ posters in their windows Rent strikers were also known to picket empty houses to prevent them being let to new tenants who had agreed to pay the inflated rents.

As many men were away at the war or engaged in other industrial battles campaigning for shorter hours, higher wages and better working conditions, women were often at the very forefront of the rent strike movement.

A banner raised during the Mary Barbour statue unveiling

Female protestors often devised clever strategies to prevent evictions from being carried out. The women utilised the design of Glasgow tenements to their advantage. If strikers were notified of planned evictions in advance, they would pack into the targeted close to prevent officials from entering and securing the tenants from homelessness.

In order to guard against unexpected arrival of officials, one person was posted in the close to warn of trouble and then if an official arrived, they raised the alarm by shouting, banging pots and pans or blowing whistles. According to reports in the Forward newspaper and corroborated by campaigner Helen Crawfurd in her diary entries, women would come running into the tenement close with bags of flour, rotten fruit, and even wet washing and would throw these items at the officials coming to evict tenants, forcing them out of the close.

The rent strike movement in Glasgow gained even more momentum when it obtained the support of Dave Kirkwood, the convenor of shop stewards at Parkhead Forge. He wrote a letter to the Town Clerk of Glasgow highlighting the housing conditions in the eastern districts of Glasgow.

He declared: “National demands have added thousands to the number of workers in Parkhead Forge with a consequent increase in domestic overcrowding. Property owners taking advantage of this have been increasing rents and the tenants have no means of preventing this unless by organised refusal to pay the increase. As this might lead to the eviction of one or more families the men here wish to make it perfectly clear that they would regard this as an attack on the working class…”

The rent strike peaked in October 1915, with an estimated 30,000 participating. However, a pivotal moment of the movement came on November 17, when a Glasgow landlord named Mr Nicholson, hauled 18 rent strikers into a small debt court.

In response to the legal action, the Housewives’ Committee immediately organised a mass march of rent strikers to the court and, as they marched in their thousands, industrial workers left their jobs and joined in the protest. The protestors became known as “Mrs Barbour’s Army”.

When the protestors reached the court in Brunswick Place in Glasgow, they bombarded the Sheriff with their statements, with most strikers threatening industrial action if the cases were not withdrawn. Eventually, the sheriff conceded and urged the landlord to withdraw his cases against the rent strikers.

Several huge demonstrations were planned for November to demand that rents be frozen at pre-war levels. However, fears over larger civil disturbances and the serious threat of huge industrial action and work stoppages forced the UK government to take action.

The protest was seen as a momentous victory, not only in Glasgow but all over the UK, as on November 25th 1915, the government introduced The Increase of Rent and Mortgage Interests (War Restrictions) Act which restricted increases in rent and the rate of mortgage interest during the first world war.