Cockburn Association: Edinburgh – The Expanding City

Edinburgh heritage body the Cockburn Association has launched a series of thought-pieces under the heading Our Unique City: Our Past, Our City, Our Future to generate a civic conversation that looks to address the many challenges facing the capital now and in the immediate future.

Paper Four – The Expanding City – considers the impact of physical growth on the land and amenity.

Background

Edinburgh is going through a period of expansion that is arguably unprecedented since the inter-war period when the built-up area doubled. The National Records of Scotland projections for 2014-2039 anticipated that Edinburgh would see a population increase of 21%, while that for Midlothian would be 26% (the highest rate of growth in Scotland) and 18% for East Lothian. This reflects a mix of market driven and public policy factors; like all projections, the figures depend on assumptions that may or may not prove reliable.

The Strategic Development Plan for the city region –South-East Scotland Strategic Plan or SESPLan for short -reflects Scottish Government (SG) policy. It states that “over the next 20 years, most growth will be focused in and around Edinburgh and in indicative ‘Long Term Growth Corridors’” and that up to 2030, it is likely to be on “land already identified in existing and proposed Local Development Plans”. This could severely damage the Green Belt and identity of settlements.

The growth corridors are to the east and south-east of Edinburgh; around Leith/Newhaven/Granton (linked to the tram route), and to the west of the city. Following SG policy, the intention is that “the City of Edinburgh will meet a larger proportion of the region’s housing need than in previous plans. It is asserted that this may help reduce commuting by car and transport related carbon emissions, as well as making best use of existing infrastructure.

Concerns from civil society about edge of city growth have been focused on three related matters. The first of these is a desire to protect the existing greenbelt and associated prime farmland. Related to this has been the way in which open space has been lost through permissions granted (sometimes on appeal) for developments on greenfield land while vacant land (brownfield) within the city has been left undeveloped. Finally, the quality of much new development is seen as falling short of best European standards in terms of design and sustainability.

The predictions

SESPlan will significantly shape the agenda for the next Local Development Plan whose production and consultation will follow as soon as it is approved. What seems clear is that much of the case for ambitious housing targets rests on assumptions about migration into the city, including a continued growth in the student population. Questions also need to be asked about the need for further land releases given the significant amounts of housing land that has not been developed during the last decade due to lack of market demand and austerity. For example, parcels of land consented for housing development decades ago remain to see a single dwelling built. The South East Wedge, released from Green Belt in an earlier Lothian’s Strategic Development Plan in the late 1990s still hasn’t reached its development objectives.

The adoption of a growth corridors approach may give some flexibility if actual development falls short of, or exceeds, expectations. However, the Local Development Plan needs to be proactive in prioritising sites for growth that do not damage Edinburgh’s natural and cultural heritage nor compromise the identity and quality of life of existing settlements. It should also avoiding a loose scatter around opportunistic locations that might maximise returns to developers but exacerbate car dependent commuting.

Are there known or unknown factors that might impact significantly on the housing needs and demands between now and 2030? Where should new housing be located? How big should Edinburgh become –should civil society’s views be sought? Should SG allocate development more equitably amongst Local Authorities?

The Green Belt

Local Development Plans to “identify and maintain Green Belts and other countryside designations fulfilling a similar function where they are needed: to maintain the identity, character and landscape setting of settlements and prevent coalescence; to protect and provide access to open space; and to direct development to the most appropriate locations and support regeneration.” In addition, two cross-boundary green networks are proposed –to the west and to the east of Edinburgh.

Green belts are often portrayed in negative terms as stopping the organic growth of settlements. In addition not all land within a green belt such as Edinburgh’s is necessarily in use for agriculture or recreation. However, green belts contribute significantly not only to the visual setting of the city but provide for local food networks and accessible recreation opportunities. Properly managed they can also aid biodiversity and help to mitigate adverse climate change effects through tree/woodland safeguard and enhancement. The perception is that Green Belt policies are not being followed properly and require stronger protection.

How should we protect the landscape setting of Edinburgh, and enhance the quality of open space around the edge of the city?

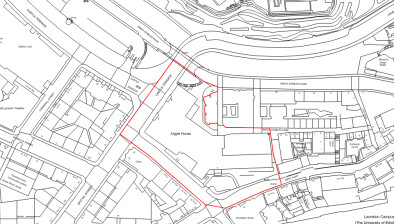

Expansion inside the city

At present, Edinburgh remains a relatively compact city, and there is general support for development on vacant of brownfield land first. The failure of past plans to deliver such development, while also conceding permissions for development on greenfield sites around the edge of the city has contributed to a loss of public confidence in the administration of planning by the Scottish Government and at local level. Furthermore, development has been allowed on valued areas of publicly-used open space within the city, as happened in Craiglockhart, for example.

The health and environment benefits of high quality public open space are widely documented, but too often have been given insufficient weight in planning decisions. The UK Shared Framework for Sustainable Development should mean that equal weight to all elements including good environment, healthy society, secure economy and good governance, supported by sound scientific analysis. With Austerity Britain and serious funding challenges for public authorities, bodies such as the National Health Service and Ministry of Defence seek to dispose of land for maximum commercial return rather than public benefit. The planning system must regain a focus on the long term public interest first and foremost, and prioritise the conservation of open spaces. The Community Empowerment Act could offer opportunities for the council to work with communities to this end.

What policies should be included in the Local Development Plan to safeguard areas of public open space within the city from pressure to commercialise their use. Should greater priority be given to while delivering development on vacant (brownfield) land before greenfield?

Quality of new development

We live in a speculative land economy. Landowners seek to maximise the benefit they receive in the disposal of land for development. Developers compete against one another to secure access to development land, pushing land prices up. The local authority seeks to secure maximum return in planning gain to support infrastructure improvements. This market-led, demand-driven pressure comes at a price, and usually that price is quality. The UK has some of the meanest space standards for new housing in Europe. Modern housing estates contain little amenity space. Is Edinburgh prepared to settle for less than the best in terms of design and sustainability in new development? Simply labelling a development “Luxury”, “Executive” or even “Luxury Executive” does not make it a good development. Indeed, too often the converse is true with much of the space being given over to excessive housing, parking and soil sealing to the detriment of site quality.

Edinburgh should aspire to be a European leader in terms of imaginative and sustainable development rather than just another place for standard houses and layouts that volume house builders can roll out in their sleep? Broad principles are obvious –protect views, water courses and trees (twiggy saplings are no compensation, though new planting will eventually help), ensure sustainable drainage systems, create walkable environments and provide quality open space not just the minimum required allocation somewhere on the edge of the site. Add in orientation, variety of house types and layouts, and use wherever possible of local and renewable building materials and energy.

The amount of projected new development means that the coming decade will stamp a significant imprint on the city for many generations to come.

How should we ensure that new development enhances rather than diminishes Edinburgh’s reputation as an outstanding city? Should new guidance be prepared to deliver better quality, holistic development in balance with the heritage requirements of the site?

To access the full report, click here.