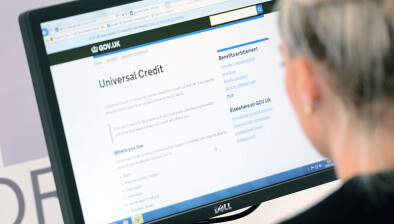

Damning report finds Universal Credit ‘may never deliver value for money’

A damning report from the National Audit Office (NAO) has concluded that Universal Credit has not delivered value for money and it is uncertain that it ever will.

Since the NAO last reported on Universal Credit in 2014, the Department of Work and Pensions (DWP) has made some progress in managing the programme but has itself admitted that it cannot measure whether Universal Credit will lead to its economic aim of getting an additional 200,000 people into work.

Universal Credit may also cost more to administer than the previous system of benefits it replaces, with current running costs at £699 per claim, against an ambition of £173 per claim by 2024-25.

The roll-out has been considerably slower than was initially intended. It was due to complete in October 2017, but after a number of problems, eight years later only around 10% of the final expected caseload are currently claiming Universal Credit.

In a particular blow, the NAO’s report states the DWP has not shown sufficient sensitivity towards some claimants and that it does not know how many claimants are having problems with the programme or have suffered hardship.

In 2017, around one quarter (113,000) of new claims were not paid in full on time. Late payments were delayed on average by four weeks, but from January to October 2017, 40% of those affected by late payments waited in total around 11 weeks or more, and 20% waited almost five months. Despite improvements in payment timeliness, in March 2018 21% of new claimants did not receive their full entitlement on time with 13% receiving no payment on time.

The Department does not anticipate payment timeliness to improve significantly in 2018. On this basis, the NAO estimates that between 270,000 and 338,000 new claimants will not be paid in full at the end of their first assessment period throughout 2018. Those with more complex cases are more likely to be paid late. The Department believes it will never achieve 100% payment timeliness because it needs by law to verify the claimants’ eligibility.

The Department expected most claimants would have enough money to cope over the initial waiting period after their claim is submitted (previously six weeks, now five). In reality, nearly 60% of new claimants (around 56,000 a month) receive a Universal Credit advance to help them manage before receiving their first payment.

Increases in rent arrears since the introduction of Universal Credit in an area, which claimants can often take up to a year to repay, have been reported by local authorities, housing associations and landlords. Some private landlords told the NAO they have become reluctant to rent to Universal Credit claimants. In three of the four areas the NAO visited and for which data was available, the use of foodbanks increased more rapidly after Universal Credit full service was rolled out to the area. This agrees with the Trussell Trust’s report showing upsurges of 30% in foodbank use in the six months after Universal Credit rolls out to an area, compared to 12% in non-Universal Credit areas.

Local organisations which support claimants and assist in the administration of the benefit have reported incurring additional costs. The Department says it has told local authorities it will pay them for additional costs associated with administering Universal Credit if they provide evidence of the expenses, but it places the burden of proof on the local authorities, uses its discretion on assessing claims and has not sought to systematically collect data on wider costs. It will therefore have no means to assess the full monetary impact that Universal Credit is having.

The programme has necessitated a number of changes which have become increasingly embedded across the Department. It would be so complex and costly to return to legacy benefits at this stage that the NAO believes there is no practical alternative but to continue with Universal Credit.

The Department must now ensure that the programme does not expand before business-as-usual operations can deal with higher claimant volumes, and must learn from the experiences of claimants and third parties, as well as the insights it has gained from the roll-out so far.

The NAO recommends that the Department should capture intelligence on claimants’ issues and the opinions of delivery partners and external stakeholders in a systematic way.

Amyas Morse, head of the National Audit Office, said: “The Department has kept pushing the Universal Credit rollout forward through a series of problems. We recognise both its determination and commitment, and that there is really no practical choice but to keep on keeping on with the rollout.

“We don’t think DWP has shown the same commitment to listening and responding to the hardship faced by claimants. Maybe a change of mind set will follow the publication of the claimant survey on 8 June. We think the larger claims for Universal Credit, such as boosted employment, are unlikely to be demonstrable at any point in future. Nor for that matter will value for money.”