Housing Champion: Laurie Naumann

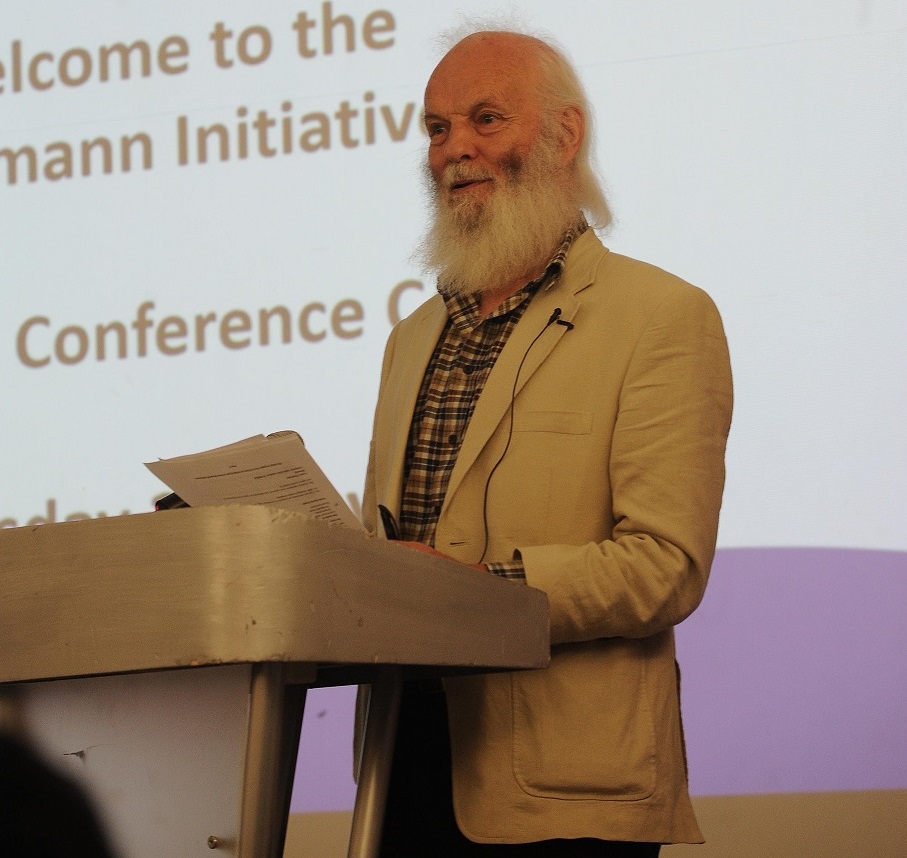

Laurie Naumann during the launch of the Naumann Initiative in 2019

Jimmy Black relives a few housing decades with Laurie Naumann, a campaigner on single homelessness, and a founder of Kingdom Housing Association.

This is a story about Laurie Naumann, who recently retired after 44 years as a board member at Kingdom Housing Association. But it’s also a step back into the past; a reminder of the times when councillors in one lowland county were given ten council house keys each to allocate personally. Unmarried daughters in Edinburgh could only inherit the tenancy of a council house in which they lived, if they promised not to get married.

Reading Robin Cook’s article in the Red Paper on Scotland is instructive. Cook was a Labour councillor in central Edinburgh in the early 1970s who had started (but not finished) a PhD on the novels of Charles Dickens. Perhaps he recognised some Dickensian absurdities in the way council housing was managed, and the Red Paper was an opportunity to move things forward.

It wasn’t just about allocations. In the 1970s, Edinburgh Corporation had 50,000 council houses, but no Housing Department, and only one qualified housing manager on the staff. There was no Housing Committee until Labour took control. Clearly, things had to change in Edinburgh and elsewhere.

Dickens himself might have recognised some of the conditions faced by homeless people in Edinburgh; for example, the 320 cubicles with chicken wire roofs in the Castle Trades Hotel, a lodging house for men which was described by one journalist as a “tinderbox”. Coughing and spitting meant TB was still a significant presence, decades after being eradicated in most of Scotland.

During the week, Fair Isle's Post Office, shop and phone box were its focal point except when the Good Shepherd ferry to Sumburgh was about to arrive or leave

This was the dysfunctional world of Scottish housing in which a young Laurie Naumann found himself, after a personal and professional journey to Edinburgh from rural Gloucestershire via Birmingham, Leicester, Brixton and Leeds. He became one of the leading figures in campaigns for structural change in the way social work and homelessness services were delivered, and for legislative change which would give people the basic human right to a home.

Laurie’s background may give us some clues about his motivation and commitment to social reform. His family were members of the Society of Friends, otherwise known as the Quakers.

The Quakers in Britain website defines their values as Simplicity, Truth, Equality and Peace. “Quakers believe everyone is equal. This inspires us to try to change the systems that cause injustice and that stop us being genuine communities. It also means working with people who suffer injustice …”

Laurie’s father was a conscientious objector who was imprisoned in World War Two, and in line with Quaker values the family worked creatively for peace. “We all went on CND marches, the early marches to Aldermaston and to London, and peace was always high on the Quaker agenda,” he recalls.

Laurie’s earliest years were spent on an organic community farm in Oyne, Aberdeenshire, followed by a move to the Garvald School in Peeblesshire, a spin-off from the Steiner community at Camphill. His parents worked as cooks at the school before moving to a smallholding outside West Linton, and then moved south to an organic farm in Gloucestershire. It was a busy life.

Members of the international volunteer team pitching in to the well overgrown ditches on Fair Isle in 1965. All the work undertaken was overseen by the local postmaster who was also employed by the National Trust for Scotland, the island's owners

Laurie said: “We had thirty dairy cows which, to start with, we milked by hand, as there was no electricity on the farm. The dairy was the critical thing, that was our main income from the sale of milk for Cadbury’s chocolate. We grew potatoes, neeps and carrots. It was hard physical work although it didn’t seem like that at the time.”

Laurie was educated in Steiner schools in Edinburgh and Gloucester, and his last year at school was in Nuremberg.

Back in the 1920s a Quaker and pacifist called Pierre Cérésole created international work parties of volunteers to provide help to communities in the aftermath of the first world war; this developed into the International Voluntary Service based in Geneva with branches around the world, and Laurie got involved. In 1965 he found himself on Fair Isle clearing abandoned peat drainage ditches and generally helping out.

“I went at the end of August and it was glorious that year,” he remembers. “It was a wonderful and memorable experience.”

Fifty years later he returned to Fair Isle and was pleased to note the sheep dip he helped to build is still in use. (You can read more on the IVS website).

You can't see it, but the water started flowing pretty quickly so essential to start digging at the lowest point. This was very close to the new sheep dip also being built by the volunteers. Laurie Naumann with another volunteer

It was time to find a career. Laurie said: “After two or three work camps I was thinking … what shall I do? I didn’t go to university at that point and I vaguely thought social work would be interesting.”

So Laurie began talking to people about how to get into social work, and he got interested in probation, partly inspired by his father’s experiences in prison and, later, as a prison visitor. He was told to get some experience in advance, and he spent a year in Birmingham at one of the first hostels in the UK for ex-prisoners.

He said: “The most valuable thing I learned there was what not to do, and yes, how not to treat people. The warden was very rigid, and inflexible about staying out late at night or staying in bed in the morning if you didn’t have a job to go to. The couple who ran the hostel had no previous experience, and it was really quite embarrassing.”

Laurie found some support from a fellow Quaker, Mike Binks. who was a probation officer working in Birmingham prison and a member of the board which oversaw the hostel. “I could go and cry on his shoulder,” he added.

He persuaded Laurie to stay for a full year, during which he applied for social work courses and was accepted by Leicester University for a two-year course combining probation and child care.

The sheep dip under construction by volunteers

The course involved practical placements, and Laurie went to Brixton to work in an innovative hostel for “drunken offenders”. That introduced him to some of the issues he would face in his first job in the Probation and Aftercare Service in Leeds, working in a large housing scheme on the east side.

Laurie explained: “A high proportion of my ‘clients’ were teenagers. A number of colleagues and I were concerned about the very routine way we were working, just seeing people, and wondering what we were actually managing to do. So we’d go out into the country, go off at weekends youth hostelling in the Dales … I doubt it would happen in the same way now.”

Alcohol abuse and dependency were proving a key issue, and Laurie attended a conference on the topic where he met Ray Flint, from Edinburgh, who was working for the Grassmarket Project Team. They were about to set up a hostel for ‘drunken offenders’ and needed a field social worker to liaise with hospitals, courts and the police. Laurie was invited to apply, interviewed, got the job and found himself, in 1973, at the start of a very significant time in Scottish social work and housing.

The hostel was in Thornybauk in the Tollcross area.

Laurie said: “Our ideal was that people would come out of hospital to the hostel and we would get them housed. But the relationship then was not good between Social Work and Housing, although they were both part of Edinburgh Corporation.

The sheep dip in 2015 and still in use on occasions

“It sounds ridiculous now, but we actually talked about Social Work buying properties in Muirhouse or Pilton, and our men … it was all men … would be able to move into houses. That never materialised, |I’m glad to say. Really, it would have been quite inappropriate for Social Work to be managing houses.”

Laurie’s boss was Peter Bates, later director of Tayside’s Social Work Department. One day he told the staff they’d be meeting someone ‘very important’. That turned out to be Councillor Cook, who seemed relieved to find some kindred spirits.

It was at this time that Laurie became much more involved in the whole issue of the Edinburgh lodging houses, all but one being in the Grassmarket area. The Grassmarket Project persuaded the newly established Health Board to support a survey to find out more about the GP registration status of people who lived in hostels, and using volunteers managed to gather information from just over 1,000 people on one night.

For perhaps the first time there was a proper understanding of who lived in the hostels, how they got there, what age they were and how long they had lived there. That new understanding brought a homeless persons’ GP clinic into the Cowgate, serving hostel residents until the time when the old lodging houses were closing.

While still at the Grassmarket Project, Laurie became involved in a survey of all 53 Scottish housing authorities for a report called ‘Letting In Single People’. The report revealed hugely restrictive and inconsistent practices across councils for single people looking for a home, many of which effectively excluded whole groups of people from council housing.

(from left) Bill Banks, Cllr Judy Hamilton, Laurie Naumann and Gavin Smith launched the Naumann Initiative in 2019

“Nithsdale was the most extreme,” Laurie highlighted. “A woman had to be 50, and a man 60 or 65, I can’t remember exactly, just to get their name on the waiting list. The receptionist would simply turn you away, there was no point in applying. At the other end, Glasgow accepted 16-year-olds, as did North East Fife which was held up as a good example.”

The Letting in Single People report was the basis for an effective campaign which Laurie continued after his appointment as director of the Scottish Council for Single Homeless. Laurie and his colleagues at SCSH were influential in campaigning for the Housing (Homeless Persons) Bill to include Scotland, persuading the Scottish Office eventually to create and publish the homelessness Code of Guidance, and in opening council house waiting lists up to people aged 16 or over.

Care in the Community is another area where Laurie and his SCSH colleagues made a significant contribution. Laurie himself takes up the story in an (edited) email sent to Scottish Housing News.

“In the Grassmarket Project, we got a bit of a name for being ‘social work specialists in homelessness policy’. Towards the end of the Housing (Homeless Persons) Bill’s progress through Parliament, the Scottish Central and Local Government Statistical Liaison Committee set up a sub-committee to recommend how statistics should be collected by local authorities on the homeless people approaching them under the Act. Sandy Murray from Aberdeen and I were the two social work members of that sub-committee.

“We picked up the issue of people who were homeless in long-stay hospitals and in prisons. With long-stay patients, we did an investigation into psychiatric, geriatric, learning disability and physical disability hospitals around the country.

Jennifer Reilly and Agnes Bicket were the first to be hired to work for Kingdom through the initiative

“We asked to meet with the staff most knowledgeable about discharge plans for patients with uncertain accommodation arrangements, and whether there were any patients in the hospital simply because there was no suitable housing available in the community.

“Lennox Castle, Glasgow’s principal Learning Disability hospital could not think of any of its 1,200 patients who would manage in conventional housing, even with support. On the other hand, the medical director of Edinburgh’s equivalent hospital, Gogarburn, said every patient could be discharged with the right support in the community, and she was, in principle, in favour of closing down the institution immediately.

“This relatively small piece of basic research proved invaluable in generating discussion about the need for a community care policy in Scotland in the early 80s. In England there had been a fairly recent Department of Health announcement with formal guidance and a financially backed plan to close long-stay, especially learning disability, hospitals, but Scottish Office ministers took the opposite line and said that there was no problem to be addressed!

“SCSH then took a lead role in organising and then servicing what became the Care in the Community Scottish Working Group with representatives from professional associations including housing, social work, medicine, nursing, CoSLA, SFHA, CIH, Directors of Social Work, specialist national care organisations and others.

“I was secretary to the Working Group which must have continued for about ten years until there was a change of heart in the Scottish Office. On reflection, I think that the Working Group did have quite an impact and very much helped to achieve the positive changes that were eventually introduced. Whilst there were obviously still niggles, housing was brought on board to play a key and integral part, and has often taken the lead, in the process of making community care work in different parts of Scotland.”

%20Linda%20Leslie,%20Freya%20Lees,%20Laurie%20Naumann.jpg)

Laurie with fellow Kingdom board members Linda Leslie (left) Freya Lees

Outside SCSH, Laurie has made a huge contribution to the founding and development of Kingdom Housing Association. Starting with the replacement of the last homeless persons’ hostel in Fife, Kingdom now has over 6,000 houses. The association has financial muscle too, having negotiated in 2018 a private placement loan of £85 million to finance development.

Among other things, it has an innovative employment project called the Naumann Initiative which helps homeless people into both housing and work. There is also supported accommodation, with a recent example being the conversion of the historic Hunter House for five flats, a part of the Government sponsored rapid rehousing plan.

It’s been hard work… forty odd years of reading the Kingdom board papers on Monday nights. He said: “Reading the papers took longer than attending the meetings themselves.”

Laurie and I had a long, wide-ranging conversation, sitting looking out over the Forth from his home in Kinghorn. There is far more to Laurie’s life and work than we could ever cover here. Given his family origins as Quakers and peace activists, I asked him if he had lived the life he wanted to live. His answer was considered, and modest.

“I don’t think I ever planned anything quite like this. It’s been in some ways rather extraordinary. For example, signing a contract for £85 million is something I never thought I would do. I think in regard to both SCSH and Kingdom, I have contributed something. Some things might not have happened otherwise. I do think my housing contribution has been worthwhile.”