Jon Kiddie: Homelessness and judicial review – a missed opportunity for reform

Jon Kiddie

Jon Kiddie, an advocate at Terra Firma Chambers, analyses concerns over the suitability of judicial review for challenging local authority decisions on homelessness.

I recently gave a webinar presentation on the topic of homelessness and judicial review. Afterwards, discussion immediately focused on a question I had posed regarding the suitability of judicial review for challenging local authority decisions on homelessness. The consensus indicated a concern that judicial review may well not be fit for purpose. In this article, I shall analyse that concern further.

Judicial Review in Scotland

By now, the procedure for judicial review is a well-established feature of our Scottish court system, while the body of jurisprudence underpinning it is substantial and constantly evolving. Moreover, a recent overhaul by the Courts Reform (Scotland) Act 2014 has consolidated and clarified the procedure, e.g. by introducing a default three-month time limit, and a sift stage where the applicant must show the case to be suitable for judicial review with a reasonable prospect of success.

There can be no doubt that judicial review has proven itself to be an important and effective remedy. It is deployed frequently. For example, it played a crucial role in the prorogation debate of 2019, where applicants challenged the UK Government’s decision to shut down Parliament ahead of Brexit. In that case, the Inner House of the Court of Session demonstrated its willingness to intervene in the executive’s ‘stymieing’ of democracy, a judgment that the UK Supreme Court later endorsed unanimously.

At the heart of judicial review is what is sometimes called the tripartite concept, i.e. where a superior institution delegates authority to a subsidiary to make decisions affecting those on the receiving end.

In a sense, local authority decisions on homelessness fit this paradigm well. The superior institution is Parliament, which has enacted the Housing (Scotland) Act 1987, and thereby delegated to local authorities the authority to make such decisions, which in turn affect applicants.

And, there is a persuasive argument that judicial review is not suitable. Thus, it should be replaced with another procedure in front of another forum, which would better fit the purpose and needs of court-users. By no means does this denigrate the rights of aggrieved applicants by denying them access to the Court of Session. Quite to the contrary, it actually enhances their rights by making justice more accessible to them, and more affordable.

Homelessness & Judicial Review

The prorogation debate was one of fundamental nationwide constitutional importance. Thus, it was only right and proper that it should be resolved by our highest courts. However, the question remains as to whether the self-same procedure is really suitable for much narrower decisions on homelessness — notwithstanding how closely these might fit the paradigm of the tripartite concept.

Here, some basic appreciation of the mechanics of local authority decision-making in such cases is useful.

Essentially, every Scottish local authority has a duty to receive applications from individuals residing within its area, whereby they may request rehousing on grounds of homelessness. The local authority has a duty to investigate each such application, to assess it (in line with certain criteria), and then to issue a decision, i.e. on whether or not the local authority considers the applicant to qualify for rehousing on this basis. If so, then the local authority will arrange that an offer of accommodation be made.

On the other hand, in the event of refusal, the applicant has a right to ask the local authority to undertake its own internal review. Typically, the review decision simply upholds the original decision.

These are the essentials of the relevant legislation, being Part II of the Housing (Scotland) Act 1987, as amended. Once this process is exhausted, the only means of challenging an unfavourable decision is by judicial review. And, the time limit for getting this into court is only three months.

A lot needs done in these three months. This includes: finding a willing and suitably experienced solicitor; finding a suitably experienced counsel; ingathering and putting together all the various bits and pieces of paperwork required for legal aid; applying for legal aid (which often entails a back-and-forth running debate with the legal aid board regarding the merits of the case); instructing counsel’s opinion; ingathering all the necessary evidence; drawing up the petition; and then serving it.

And, while all this is going on, the applicant might face additional severe disadvantages, including: lack of reliable postal address; lack of internet; lack of mobile phone credit; substance abuse; mental health issues; and, of course, actual homelessness and rough-sleeping — and the vulnerability attendant on same.

Then, when the case eventually proceeds to court, the applicant may have to attend to give evidence. At the very least, they have a right to attend any hearing where their rights and future quality of life hang in the balance. Yet, the only venue for hearing judicial review is the Court of Session. And it only ever sits in Edinburgh.

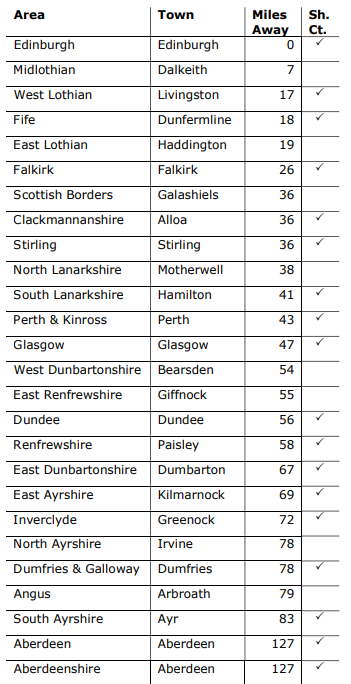

To put this in perspective, Scotland has a geography of some 31,000 square miles over 32 local authorities. Here is a table showing the relative distances of their principal towns from the capital. Those with a sheriff court inside their limits are indicated accordingly:

Thus, it can be seen that a quarter of principal towns are situated in excess of 100 miles away, while our island communities lie in the order of 250 to 350 miles distant. Moreover, the farther from conurbations, the more rural the terrain becomes, and the slower the transport system. For example, for a resident of Shetland, it could easily take two whole days to commute to Edinburgh. Yet, of these 32 principal towns, 23 have a sheriff court situated within them, while the remaining nine are served by at least one sheriff court in a nearby outlying town (some by more). For example, Glasgow Sheriff Court encompasses several areas, while Highland has sheriff courts in Fort William, Oban, Portree and Wick (in addition to Inverness). Significantly, each of the three island towns has a sheriff court, while the Outer Hebrides also have one in Lochmaddy (in addition to Stornoway).

In England & Wales, the situation is perhaps somewhat more even. There, judicial review is the domain of the Administrative Court, which is part of the Queen’s Bench Division of the High Court. However, unlike the Court of Session, which only ever sits in Edinburgh, the Administrative Court may convene in London, Cardiff, Leeds, Manchester, Birmingham and Bristol.

Court Reform

Over the course of 2007—2009, the Scottish Civil Courts Review (chaired by Lord Gill) undertook an extensive review of Scotland’s entire civil justice system. Its terms of reference included the cost of litigation and judicial specialisation. In 2009, it reported its recommendations, including the establishment of the Civil Justice Council for Scotland (CJCS), which was given effect by the Scottish Civil Justice & Criminal Legal Assistance Act 2013. The CJCS continues to monitor the system on an ongoing basis, and must have regard to certain fundamental principles. These include access to justice.

Much of the foregoing review process was, in turn, put into effect by the Courts Reform (Scotland) Act 2014. Its impetus consisted of diverting a weighty volume of litigation, including whole categories of it, away from the Court of Session and towards other courts, including the sheriff courts and our two newly created additional national courts, being the Sheriff Appeal Court and the All Scotland Sheriff Personal Injury Court. Meanwhile, certain other litigation was shifted out of the sheriff courts, e.g. the whole private tenancies regime was relocated into the First Tier Tribunal (Housing & Property Chamber).

In principle, this reshuffle made an enormous amount of sense. For example, whereas in the past certain law firms might routinely threaten to raise even low-value claims at the Court of Session simply to intimidate opponents into settlement, now only claims worth over £100,000 are competent there. It also makes sense to have specialist personal injury judges, specialist appellate judges, and specialist commercial judges.

And, of course, if a legal issue arises of fundamental nationwide constitutional importance (e.g. prorogation), then it makes sense to have this dealt with by the highest court in the land. However, after the tide of reform had surged over the watermark and settled back down upon our brave new legal landscape, the homeless applicant was still left with only one option — judicial review at the Court of Session. The highest court in the land. Also, in many cases, the farthest away. And, in each and every case, the most expensive by a long shot.

This was a missed opportunity for reform that would have pushed the doors of justice wide open for a significant proportion of our population, and some of the most disadvantaged and vulnerable at that. It would have given them a chance for a vastly better quality of life. It would have given them hope.

Meanwhile, the Scottish Government has pledged to eradicate homelessness, and this according to certain reports by as soon as 2023. Absent a truly effective, readily accessible remedy — well, good luck. Let’s just see how local authority homeless departments go about their business when the watchman is hundreds of miles away with his back turned.

The Burden of Proof & the Man in the Cheap Suit

Although nowadays in this country the use of judicial review has increased, and awareness of it has improved, nonetheless it is perhaps still not regarded in the same way as in other parts of the world. In essence, when the Court of Session exercises its supervisory jurisdiction in judicial review, it is really acting as a constitutional court. However, the Court of Session is not really thought of, let alone spoken of, as a constitutional court — not like the Supreme Court of the United States, for example.

Even the English & Welsh equivalent, as said, bears the title of Administrative Court, which more closely aligns with its actual function. One consequence of this situation is that, rather than being considered as a form of constitutional remedy, judicial review tends to be considered as just another form of procedure available at the Court of Session. And, it tends to be taught that way too. This is a pity. If it were considered alongside other similar (quasi-)constitutional remedies, and taught as such, i.e. as part of constitutional law, then perhaps closer attention would be paid to these other remedies too inasmuch as they exist elsewhere in our justice system. And, as it happens, these are plentiful, including summary applications to the sheriff court and statutory appeals to that jurisdiction as well as to tribunals.

When one considers these, one begins to realise how closely they sometimes resemble judicial review in nature and effect. For example, licensing decisions are taken by licensing boards in the exercise of delegated authority, and routinely challenged at the local sheriff court. Here, the paradigm of the tripartite concept is virtually identical except for venue, accessibility, and cost.

In conclusion, it is hardly any wonder that so few homelessness cases ever actually reach the Court of Session. By contrast, licensing matters are litigated routinely almost every day up and down the country.

Of course, let us not forget that local authorities are under tremendous pressure, where demand for housing constantly exceeds availability. Will they do their job properly when, chances are, unsupervised, they realise they can get away with doing it however suits the exigencies of this situation regardless of applicants’ actual legal rights and practical needs? 2023 is only three years away. But this is a case for reform that is long overdue.