Ken Gibb: Localising Local Housing Systems Analysis in Govan

Professor Ken Gibb

UK Collaborative Centre for Housing Evidence (CaCHE) director Ken Gibb shares insights on Local Housing Systems Analysis (LHSA), its impact on Govan, and how it’s driving regeneration in Glasgow.

The Local Housing Systems Analysis Backstory

In the early 1990s, colleagues at the University of Glasgow, working with Scottish Homes, developed a housing planning model to guide sub-national housing investment for housing associations, known as local housing system analysis (LHSA). For a decade, this framework became the statutory evidence base for local housing strategies after the 2001 Housing (Scotland) Act. We also exported the thinking to Wales and to Northern Ireland. I spent probably 20 years training housing staff in all three countries on the merits of LHSA as a tool to better understand local housing and to inform local policymaking.

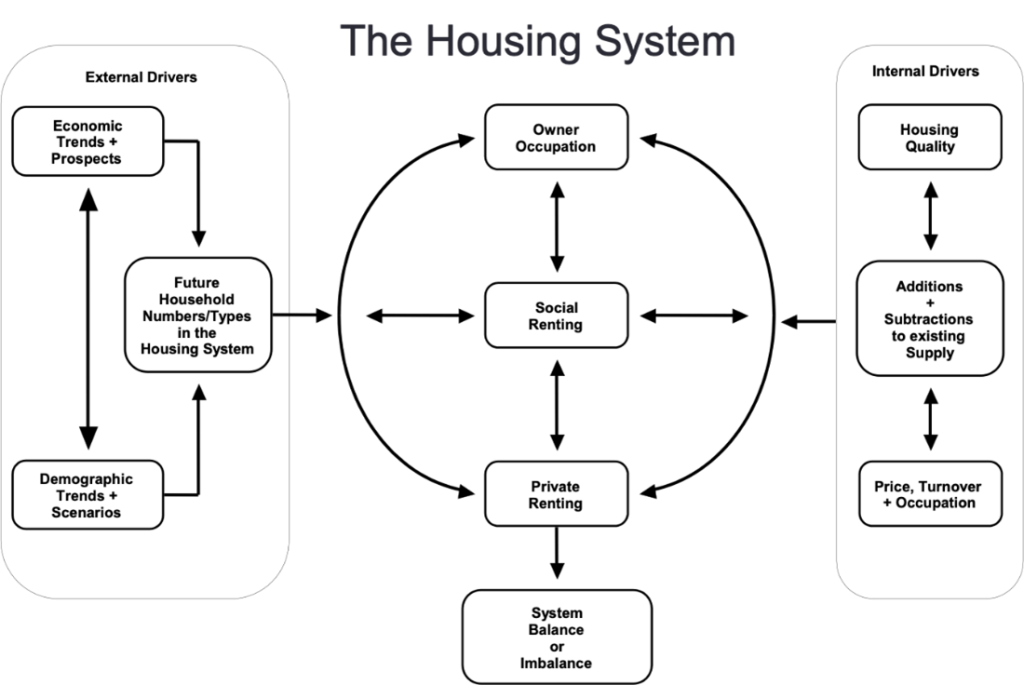

Led by Duncan Maclennan and Tony O’Sullivan, LHSA was based on systems thinking, a little core housing economics, and also robust empirical social science. It was also pragmatic, recognising that we must deal with the reality of incomplete and imperfect knowledge or data, and instead make informed judgments based on an audit of data, and by triangulation, guesswork and analysis of wider available evidence.

Typically, LHSA worked at the travel-to-work area level, the metropolitan region or the housing market area – it was rarely, if ever, functionally defined by local authority boundaries. It asked in what context the housing system operated and what the demographic and economic drivers of local housing were. It examined closely how the internal workings of the housing system functioned and ultimately looked at a series of key indicators to judge whether it was balanced or imbalanced (and what, if any, corrective interventions were suggested by the evidence).

Localising LHSA in Govan

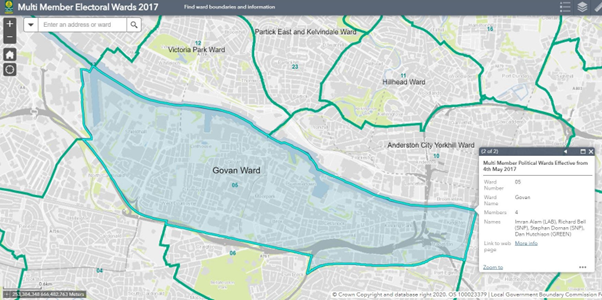

In early 2023, Matt McNulty from GCC’s housing strategy team, in partnership with the three community-controlled housing associations i.e. Linthouse, Elderpark and Govan (and, later, the University of Glasgow), asked if CaCHE might attempt to undertake an LHSA research process for Govan on the western edge of the south side of Glasgow.

Source: GCC

The reasoning behind this request was a widespread sense that Govan was approaching a tipping point with the potential to see significant investment in market and social housing. This would amplify a confluence of positive factors: Govan’s cultural heritage and strong sense of community, its economic strength as a jobs focus for the city-region, its untapped land supply, the advent of significant University investment in the GRID, the continuing opportunities created by the Queen Elizabeth University Hospital and associated clusters, the connectivity to the west end brought by the new pedestrian bridge opened in the summer of 2024, and a further catalyst in the case of the Transforming Communities: Glasgow site for private and social housing led by the City Council and the Wheatley Group at Ibrox/East Govan.

The research proceeded through a scoping study, a data audit, an audit of land sites, and a combination of qualitative key actor interviews, as well as considerable secondary data analysis, frustratingly all in advance of the delayed Census. We decided that this work would not have new primary data inputs in the form of household surveys but we did undertake novel secondary data analysis including a snapshot of private housing market activity, a sense of current housing need in Govan, as well as comparative analysis of developments in the locale in relation to the newly connected Partick neighbourhood. The main report is now published on the CaCHE website.

What are the key takeaways?

First, an interviewee said Govan’s transformation required a seed, spark or catalyst. Govan is at a development (and hence regenerative) tipping point driven by enhanced external connectivity, relative affordability compared to the city level, investment in the GRID and through the large-scale investment coming in Ibrox/East Govan. These catalysts for change also have further sites to work with across Govan. However, there needs to be joined-up strategic leadership within a built environment investment framework that makes good choices over the zoning (and re-zoning) and phasing of development for housing, for GRID, and for local employment/business opportunities.

Second, stakeholders should learn from Gorbals, Sighthill and elsewhere in Glasgow in terms of what works. Equally, they need to work with local Govanites to learn lessons about how and why past regeneration efforts have had mixed success and how future efforts might do better supporting local people and communities. A joined-up strategic approach could do much with this window of opportunity.

Third, stakeholders can learn from systems analysis both in terms of the fundamental interdependence of different tenures, mixed housing and development decisions and the consequences for adjacent areas and place development, but also around the importance of initial conditions and path dependency. History matters and is essential to understanding places like Govan.

Fourth, a Glasgow-wide perspective matters in looking at the case for housing investment in Govan – there is a discount to first time buyer homes and potentially student rents south of the river and that can help newly-adjacent neighbourhood markets without sufficient developable space like Partick. Govan is deeply embedded in Glasgow but that could and should have a reciprocal benefit for Govan if land and development could be wisely developed for housing, employment and innovation.

Specific early steps that could support local Govan people benefiting from these investments include: embedding GRID further in the local area through infrastructure support, by partnering in schools and through training/skills opportunities. Using procurement to maximise construction benefits for local workers, apprentices and trainees. Additionally, there is the need to retrofit and upgrade considerable volumes of older tenements in the years ahead. By creating local jobs, skills and more spending power, investing more in pedestrianisation and the walkability of Govan, this can all help uncouple the ward from negative perceptions and stigma. This will also encourage commuting workers to move to new housing in Govan.

Finally, the rental market offers opportunity: housing associations can acquire vacant PRS stock for affordable housing through acquisition (often taking stock on in closes where there is already housing association presence); supporting the growth and success of local mid-market rent, and, via the University presence and the new bridge, to support possible further investment in student accommodation (and make the case for that to be more affordable relative to student accommodation investment already at planning in the city centre).

Does it make sense to localise LHSA?

Govan has well defined physical boundaries via the river, the motorway, the city council boundary with Renfrew, and the hospital complex itself. It is nonetheless deeply enmeshed in the city-region economy as a jobs hub and the ward is open and exposed to wider general city level influences on spending, investment, housing and footfall. It clearly makes no sense to think of areas like Govan as sufficiently standalone housing market areas.

But we should not, therefore, disregard the notion of a localised LHSA. With expectations set at the right level, working from an LHSA framework combining local data with a wider sense of the local impact of the regional housing market and economy – there are useful insights to help us understand localised housing systems within bigger conurbations. We also think Govan and other locations in and around Glasgow would benefit massively from a new city-region level Glasgow-centred LHSA. But that would be another project.

This blog was originally published on the CaCHE website