Margaret Corrigan: Fuel poverty vs carbon reduction and the soaring cost of energy

Margaret Corrigan

Margaret Corrigan from Cunninghame Housing Association’s Lemon Aid Fuel Poverty & Advisory Service provides some detail on the issue of low carbon heating systems vs affordability for tenants.

Energy prices have risen at unprecedented rates in the past year, and it is estimated that a further 800,000 households have or will fall into fuel poverty in Scotland since the last increase of 54% in April 2022. It is not just the burden of the actual unit costs increasing, standing charges have increased too, as a levy on households to help pay for all the failed suppliers during the crisis.

Many believe that this should be done through general taxation and should not be a burden on those already struggling to pay higher costs.

The reality for households is bleak.

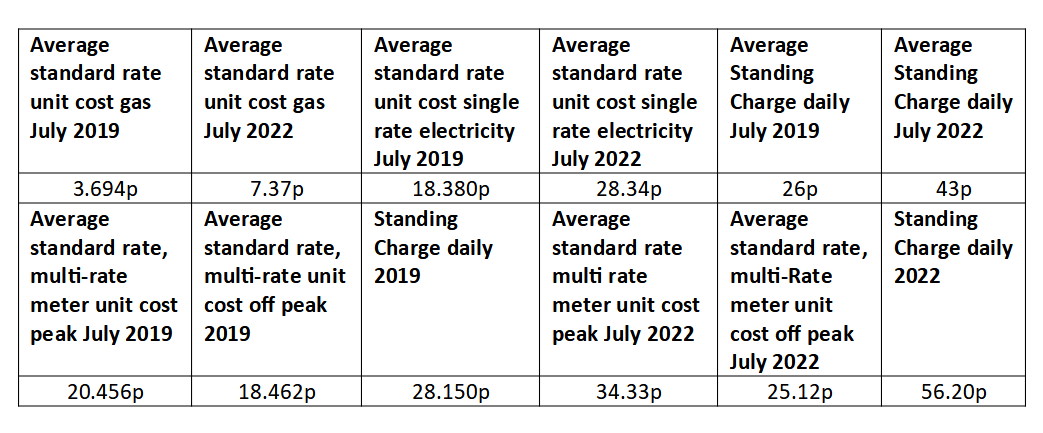

Below is a table of historical price per kWh on OFGEM price cap standard variable tariff and the cost today on OFGEM price cap standard variable tariff. There will be another significant rise again in October and again in February as OFGEM have changed the time frame in which they review the price cap (the maximum that can be charged on a standard variable tariff).

An average household using 14000 kWh gas per annum would be circa £663 per year.

Average household using 3200 kWh electricity per year would be circa £708 per year.

Both include Standing Charge.

Multi Rate meters are designed for historic all electric on storage heating. They give 2 or 3 rates. A peak day rate, an off-peak rate, and if there are three rates, there is a control rate which heating and hot water come from. Historically the off peak and control rate were much lower than the peak rate to allow old style storage heaters to charge up overnight or in some cases set hours during the day. Now there is little difference at all between the cost of the rates and it is a very expensive option for all electric properties. Many of these meters are left in place when heating has been upgraded and this meter type is no longer required.

The national average consumption is circa 5000 kWh’s a year, however that does not take into account Scottish Consumption for rural and island communities where consumption is higher due to weather conditions and the fabric of buildings and a more realistic average for Scotland from experience is circa 7000 kWh a year however it is not uncommon to see consumption of circa 10,000 kWh per year. Average cost pre price increase was £2000 a year but a more realistic figure for Scotland was £2500 and up to £3000 per year in island communities.

In October it is expected that the possible increase of a further £800 has been substantially underestimated.

Households were spending this amount of money with storage heaters without having a warm home as the old storage heating systems were inefficient.

Many social landlords in off gas grid or high-rise city centre dwellings upgraded heating systems in the early 2000 to Wet Electric heating systems and while the thermal comfort was improved the cost escalated for tenants making them unaffordable. Many social landlords changed the heating but were unaware that the meter also needed to be changed to a compatible meter for the heating system which escalated costs further.

Currently many all-electric heating systems are being replaced with Air Source Heat Pumps which contribute towards carbon reduction and Net Zero. The issue is that although they give excellent thermal comfort within the home the actual annual consumption is not reduced and cost as much to run as old storage heating. It requires a single rate meter and again many upgrades are not accompanied with advice to the tenant as to correct meter type for the property and tenants are often left with historical metering for storage heating which makes the cost of heating their home prohibitive. At present average annual cost to run ASHP is circa £3000.

With EESSH2 imminent and the obligation to contribute to Net Zero there is a conflict now for landlords between low carbon versus affordability and tenancy sustainability for tenants.

In pursuit of high EPCs some Landlords are proceeding with Heating Upgrades to All Electric, without proper knowledge of the heating types, required meter types and actual cost to maintain a satisfactory heating regime within the household.

I have examples where some Social Landlords are proceeding with upgrades with a mix of heating types within one property. In this case Modern Storage along with Panel Heaters. While this achieves a high EPC rating for the properties, it makes it totally unaffordable for tenants. There will always be one of the heating types operating on the wrong meter type. Before the price increase Lemon Aid dealt with several households in this situation where their monthly payments had increased to £300 a month and in some cases up to £400.

Lemon Aid also has experience of a Local Authority installing various electric heating systems without proper research as to cost for their tenants and not getting meter types changed. These were properties where all the residents were over 75 and their bills went from £200 per quarter to £2000 a quarter. The tenants had to be compensated and the heating systems had to be removed and replaced with oil heating. This defeated the purpose of carbon reduction and cost the Local Authority and in turn Council Taxpayers a vast amount of money.

There is conflict between achieving Net Zero and Tackling Fuel Poverty and at present there is not much thought being given to affordability for normal people and instead of “a just transition” and “nobody left behind” many normal households on medium to low income or benefit dependent may be left either unable to use heating at all or be pushed further and further into debt and fuel poverty.

At present there is a global shortage of Smart Metering and suppliers are being too slow to offer time of use tariffs based on demand on the grid.

Lemon Aid were involved in a project in Dumfries with Warmworks installing Tesla Batteries. The project was a virtual network and was dependent on suppliers giving a compatible tariff so the batteries would charge at times of low demand and discharge and power the property at times of high demand. A well-known energy supplier provided a tariff, but once it was seen how much the households were benefitting from this and how little the supplier would make in revenue, they raised the price of that tariff prior to any price increases and made it as unaffordable as the tenants’ original heating source had been.

Therefore, unless suppliers are obliged to offer time of use low demand tariffs for renewable sources at affordable prices then the move towards renewable innovative projects must be paused to consider affordability for households.

- Margaret Corrigan is operations manager at CHA Lemon Aid/Fuel Poverty Services