The Margaret Taylor interview: Laurie Naumann reflects on Scotland’s progress in tackling homelessness

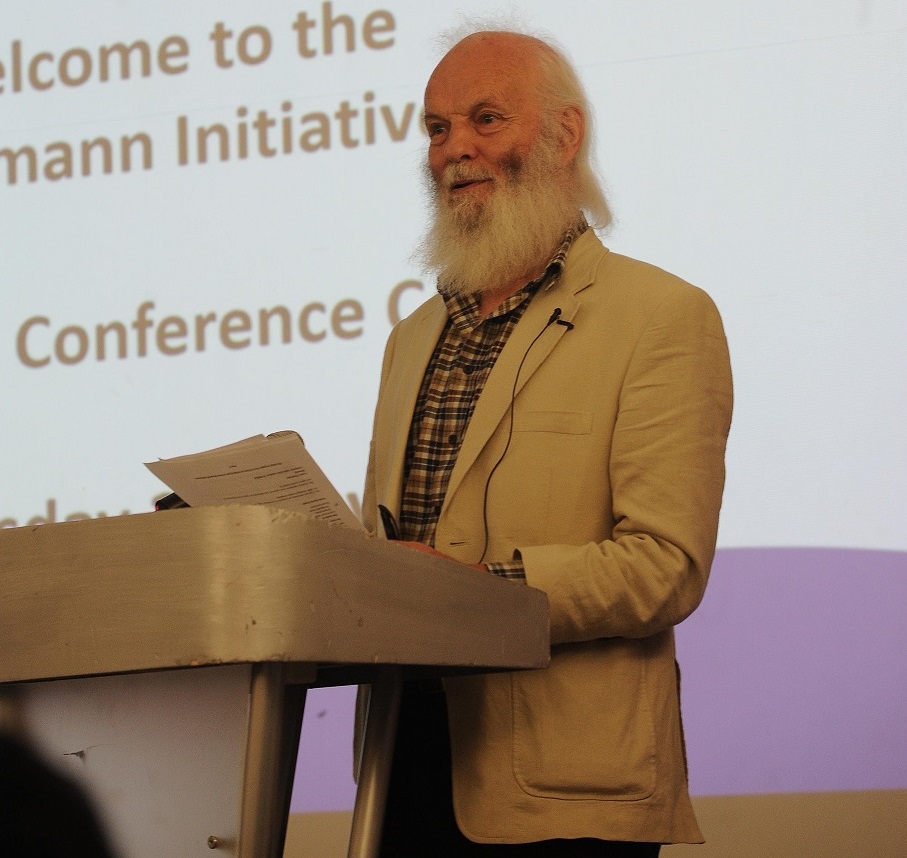

Laurie Naumann during the launch of the Naumann Initiative last year

If you have worked in the housing sector for as long as Laurie Naumann has it is only a matter of time before your name becomes immortalised. His was last year, more than four decades after he joined Edinburgh Corporation to help revolutionise the way that city addressed homelessness, when the Fife-based housing association he cofounded and vice-chairs launched its Naumann Initiative.

In homage to its namesake’s career, the purpose of the Kingdom Housing Association project is to end the co-dependent relationship between homelessness and unemployment by giving a homeless person not just somewhere to live but a means of earning a living too. So far Kingdom has been able to employ two people via the initiative - housing assistant Jennifer Reilly and tenancy sustainment worker Agnes Bicket - while the model has started to gain traction south of the border after English association PA Housing adopted it last month. That, says Laurie, is the ultimate sign that it has been a success.

“The wider interest in the initiative among other associations is encouraging,” he says.

“For many years we’ve said we would shortlist people who were homeless or who have been homeless for jobs, but we couldn’t make any commitment to giving them a job.

“The Naumann Initiative asks for homeless people to apply for the jobs and at the launch about a dozen people who fit the bill came along.

“Kingdom has made two appointments so far. One job was advertised and had about 15 applicants but they were all good candidates and they were so impressed that they appointed two.”

It is a far cry from the situation facing homeless people when Laurie took up the Edinburgh Corporation role in 1973. At that point, much of the city’s homeless population was centred on the Grassmarket in poor quality accommodation, but little was known about individual people’s circumstances and there was no co-ordinated approach to helping them. The social work project Laurie was involved in sought to address that.

“What we realised very quickly was the inadequacy of all the temporary housing that was around, but at that time social work and housing were in different authorities and homelessness was seen as a welfare problem,” he recalls.

“Homelessness accommodation was very concentrated in run-down large hostels and lodging houses in central Edinburgh and many people had been living in that accommodation for 20 to 30 years. About a third were over pensionable age; about a third had been in there for well over 10 years - casual workers who were in between contracts - then there were the homeless people, many of whom had drink problems.

“We managed, with the co-operation of the health services, to convince the housing department that they had a role to play and, with the help of the Church of Scotland, Edinburgh Cyrenians and other charities, we persuaded them that they needed to do something about healthcare.

“In late 1974 we did a one-night survey asking the residents of the hostels and people in the night shelter how long they had been there and whether they had a GP. We managed to interview just over 1,000 people in one night so got a good sample, but what we discovered was that Edinburgh was a magnet for people coming in from outside the city - people had GPs in Linlithgow, Haddington, Falkirk. Only a few were registered with Edinburgh GPs.

“That really exposed things to the health board and this was seen to be a good opportunity to do something a bit different and new. These results were so startling they couldn’t object.”

What followed was the establishment of an Edinburgh working group on single homeless with Laurie acting as secretary. That led to the creation of the Scottish Council for Single Homeless (SCSH), which in the 1970s campaigned with other organisations such as Shelter Scotland and Scottish Women’s Aid for the Housing (Homeless Persons) Act. Laurie became heavily involved in that campaign after discovering that the original private members bill that led to the act did not include any provision for Scotland.

“There was a Liberal-Labour pact in the Callaghan government, when Labour only had a very small majority,” he recalls. “One of the agreements was that the Liberals would support Labour only if the Homeless Persons Bill was included, even though it was a private members’ bill and that the legislation should extend to Scotland.

“That made it the legal responsibility of local authorities to house homeless people, but it was really only homeless families and vulnerable people - single people were left out at the outset. An abused woman on her own would be considered because she’d be classed as vulnerable but the idea that a young person of 17 should be considered was anathema.

“The Act provided for grants to voluntary organisations but they could only fund national organisations - it was expected that local authorities would fund local ones. In some local authorities, members of opposing political factions were so aghast that they united in their opposition to the legislation.

“Some smaller authorities resolved the situation for themselves by giving people a bus fare to go to Edinburgh or other large population centres. That was common throughout Scotland - in Shetland they would send them to Lerwick.”

It was through his work campaigning for local authorities to ease restrictions that prevented single people from accessing housing that Laurie became involved in the establishment of Kingdom, although that was almost derailed by funding cuts imposed when Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government came to power in 1979.

“About the same time as the implementation of the Homeless Persons Act, I’d been in touch with a number of local authorities and North East Fife and Kirkcaldy had shown an interest in what the SCSH was doing, as well as Fife Regional Council,” he says.

“The last lodging house in Fife was under serious threat as it was such a fire risk and the council was keen to get it closed because it had a plan to build a new secondary school on the site in Lochgelly. There were 44 men in that hostel, most of whom had been there for a long time. Some were Polish ex-servicemen who had moved into mining in Scotland and were then close to retirement age.

“I was called to a meeting with a number of concerned people including the assistant head of one of the schools that would be moving into the new one. We got together with the brother and sister that owned the lodging house and fortunately the overall concern was to do something about this and not put those people out on the street.”

After confirming new homes had been found in the public sector for all the men who requested one, Laurie and his colleagues put together a constitution for the organisation that was to become Kingdom, stating that its initial primary concern would be to house single people while also allocating 10% of new properties to homeless people and 10% to those who required support.

“Right at that point there was a change of government, though, and almost one of the first cuts was the introduction of a moratorium on funding for any new housing associations,” Laurie recalls.

“We unfortunately fell into that category. Langstane housing association in Aberdeen was only a few months ahead of us but it managed to get away.

“As a group there were six to seven of us and we stuck together and continued to meet monthly during the moratorium period, which was about two years. Suddenly, at the end of January 1982, I had a call from the director of the housing corporation to see if we were still in existence.”

From a handful of homes initially, Kingdom has developed more than 5,000 houses over the past four decades, the majority of which are for social rent. It invested around £60m in new affordable housing last year, now employs over 380 people and turns over in the region of £35m, across the Kingdom Group every year. The Naumann Initiative is just the latest in a line of projects it has worked on over the years to help support its mission to provide tenants with ‘more than just a home’.

Yet despite Kingdom’s progress, things are clearly far from perfect in the housing sector. Homelessness in general remains a concern and the government’s Housing First project, which aims to eradicate street homelessness by providing houses as well as wraparound care and support for those with complex addiction issues, has fallen well behind target after just one year. For Laurie there are still plenty of reasons to be optimistic, though.

“Generally, I’m much happier about the commitment that’s being made,” he says. “Even on Housing First, the government has been able to talk about it and come forward with these proposals. It’s disappointing that they’ve not been able to meet their targets, but that’s not new. Among local authorities and housing associations there’s enthusiasm to work in that way.

“To house homeless people previously you had to go through a series of supported housing - into the night shelter, into a hostel, into a small group home, but never actually into your own house; 35 years later the Housing First model has begun.

“There’s a lot of déjà vu from me because things will get relegated, especially if the crisis deepens. Things seem to improve incrementally then new issues arise, but I do generally think things are a lot better in Scotland now than they were in many areas.”