What Works Community pilot: understanding and using data

James Cartwright explores what the What Works Community pilot teams at East Ayrshire Council, Southend Borough Council and Pembrokeshire County Council learned about the value of data practices at the project’s first residential.

The first day of our What Works Community pilot residential was designed to give participating local authorities (LAs) a grounding in data practices to facilitate their ‘evidence accelerator’ challenge. The challenge we have set each LA is to develop a solution to increase the number and duration of successful tenancies in the private rental sector (PRS) for people at risk of or experiencing homelessness.

Leading the day with us was our partner Eric Reese, training director of the GovEx Academy at Johns Hopkins University’s Center for Civic Impact, whose mission is to help governments use data to make informed decisions and improve people’s quality of life. Eric designed a custom programme for the LAs to help them improve the data infrastructure and practices within their organisation and strengthen their capabilities in data quality and analysis.

“Building habits to use data and include it in your regular decision making is critical. I hope we’ve given them the tools and confidence to do that going forward and to hit the ground running.” – Eric Reese

Watch this video for a quick overview of the day from the team and participating LAs:

In advance of the residential, each LA completed an in-depth survey of their organisation’s existing data practices, evaluating the processes they use to gather, inventory and utilise data, how they select metrics, their methods of data analysis and how they communicate with data in their day-to-day work. The survey was designed to test their assumptions about their current data capabilities and provide a baseline to measure improvement as the pilot progresses.

The survey asked them to review eight data domains which then informed the structure of their learning on the day of the residential and has allowed us to tailor our offer for the rest of the programme:

Increasing access to data — creating common knowledge of the range of existing data, determining which is most critical, and sharing those datasets appropriately.

Improving data quality — identifying problems in data quality and developing improvements.

Reducing harm from data — protecting against harm resulting from data collection or use.

Problem articulation — scoping and framing your data projects appropriately for your use-case.

Selecting metrics — developing, tracking, and sharing measures for your strategic priorities.

Data analysis — effectively supporting decision making with an array of techniques.

Performance meetings — meeting to make decisions on the basis of data and analysis.

Data communication — conveying the effects of your data programme to staff and the wider public.

The responses to the survey showed differences between each LA, with some suggesting almost complete proficiency in certain areas and others believing they had almost no capacity in another. The purpose of the survey was not to achieve perfection, but to identify areas of relative strength and track change over time. It also formed the basis of our one-to-one sessions with each authority, in which we reviewed the strengths and weaknesses of their processes and asked them to identify shared challenges and obstacles.

Having reviewed the survey of data practices, the rest of the day was split into two areas of learning; data inventorying practices and data quality practices.

In the context of an LA, improving data inventorying practices can help to increase efficiency and accountability, enable performance management, reduce risk, identify gaps in knowledge and enable sharing among peers. In regard to their challenge in the PRS, we worked with our LAs to give them the tools to establish an oversight group within their organisation, define the scope and scale of their inventorying operation, catalogue relevant data assets, undertake quality checks and prioritise their collection of datasets to effectively address their individual challenges.

Equally important was helping them to consider how best to ensure and maintain the quality of the relevant data available to them. A lack of access to data, or access to poor quality data, can inhibit an organisation’s ability to undertake diagnostic analysis and engage in predictive modelling and prevention.

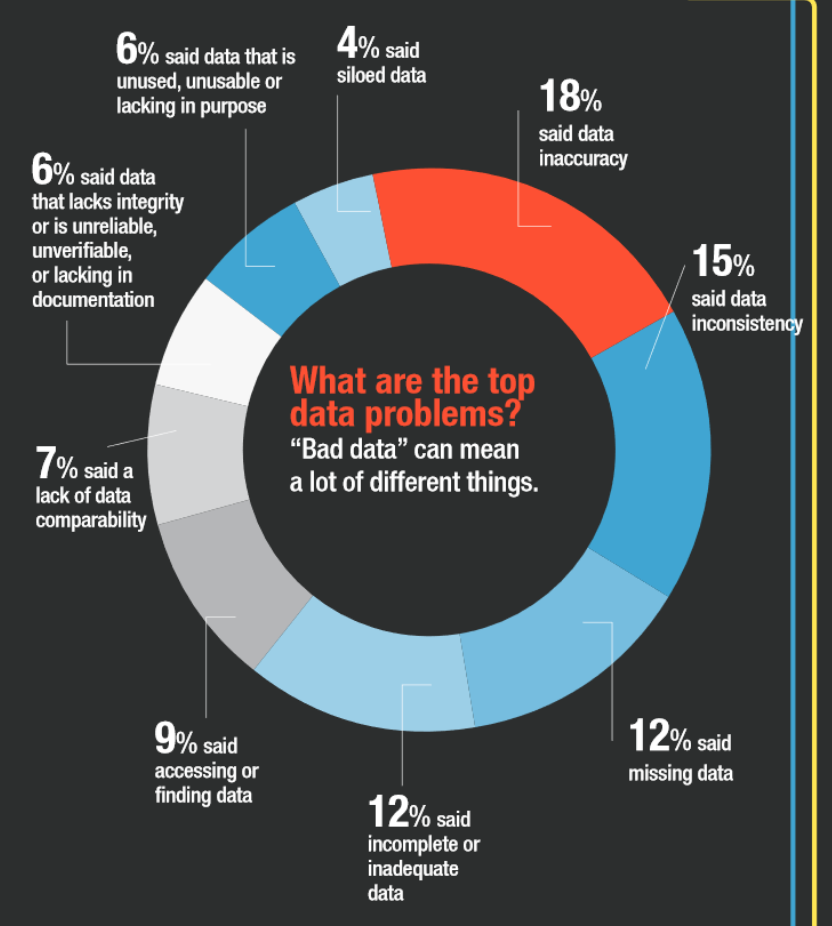

The diagram above outlines a multitude of reasons for access to poor quality data within any given organisation but, broadly speaking, using “bad data” gives rise to three potential risks:

Misinformation

When the wrong information is received by a resident or user of government services. For example, when a bus timetable contains inaccurate information on when a bus is supposed to arrive or depart.

Misattribution

When an event or activity is mistakenly connected to a cause. This is the area of false positives in algorithmic predictions, where poor data quality can be a matter of life and death. For example, many police departments across the nation are using predictive policing and hot-spot analysis to determine where crime is likely to happen. Poor quality information fuelling these models can cause police departments to draw connections between crime and certain geographic locations, producing unintended effects.

Miscategorisaton

When events, activities, or people are sorted and placed in the wrong categories based on poor quality data. As we see increasing use of algorithmic systems in government, poor data quality (including biases baked into our data) can lead to a number of problems for people, including job loss, lack of access to needed services, and incorrect child welfare decisions.

Our LAs worked through a variety of exercises designed to help them assess the quality of the datasets relevant to their challenge and identify ways in which they could be improved in order to better meet user needs.

Finally, they were tasked with creating a data action plan to take forward and develop in the next stage of the pilot and instructed in best practice for creating an implementation strategy to do so.

The teams responded positively to the residential and focus on data. They said:

“We’ve all been using data, what today has told us is that we’ve been using it in the wrong way. We’ve been using it reactively, rather than proactively. There’s so much potential to use data to inform our practice.” – Pembrokeshire team

“It was interesting to dive in and see what data really means, and how it can be used effectively to get answers and outcomes.” – Southend-on-Sea team

“Looking at the data inventories, the quality of the data we have and issues was a really useful exercise. It made us realise we have a lot of the skills already, it’s just about making best use of them.” – East Ayrshire team

Following the residential, the LA teams have taken part in ‘Data therapy’ sessions. These were an opportunity for the pilot leads to discuss the progress of their data action plans and the ways in which their findings will influence their next steps. We helped the LAs to decide which datasets to pursue, and which data values are most likely to be helpful in their research. They have also undertaken a further online data training session in data governance.

This upskilling on data is only one part of what they are learning to help them tackle their challenges. Watch this space for what happened on the second day which focused on user research.

If you’d like to know more about the What Works Community pilot, visit the webpage or email us at wwcommunity@homelessnessimpact.org.